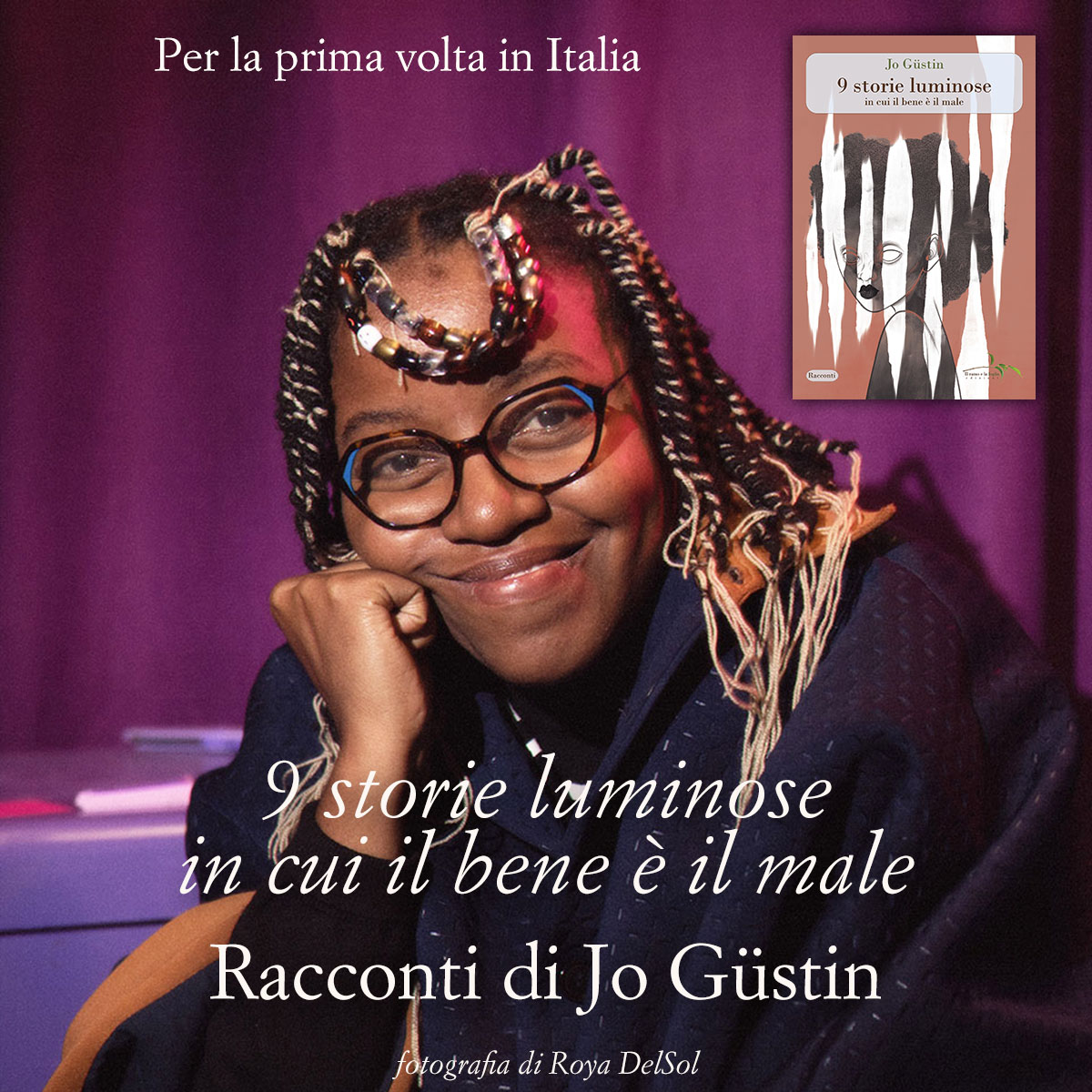

🌟 Proponiamo qui la nostra intervista a Jo Güstin, autrice di “9 storie luminose in cui il bene è il male”, per la prima volta tradotta e pubblicata in Italia (traduzione di Luca Bondioli dal francese; il libro è pubblicato in Francia da Présence Africaine Editions).

Leggi in italiano (vai) o in inglese (vai)

*

Intervista tradotta in italiano 👇

:: Ciao Jo, per la prima volta esce in Italia un tuo libro tradotto dal francese, la lingua in cui scrivi, nell’ottima traduzione di Luca Bondioli, edito da noi di Il ramo e la foglia edizioni, si tratta di una raccolta di racconti: “9 storie luminose in cui il bene è il male”, titolo quanto mai originale, edito in Francia, con il titolo “9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal”, da Présence Africaine Editions. Potresti presentarti brevemente a quelli che in Italia ancora non ti conoscono?

🎤 Ciao Italia! Sono Jo Güstin (lei/sua), sono una scrittrice, comica, regista, produttrice che usa la finzione e la commedia per il bene della giustizia sociale intersezionale (vale a dire con l’obiettivo di rovesciare i sistemi di oppressione: razzismo sistemico, abilismo, sessismo, transfobia, classismo, omofobia e specismo). Sono determinata a celebrare la queerness femminista nera in tutte le mie creazioni e a farti ridere la maggior parte del tempo, sognare a volte, e pensare tutto il tempo.

Sono nata e cresciuta in Camerun, ho studiato in Francia, Germania e Giappone e ora vivo in Canada. Scrivo in francese e inglese produzioni televisive, film, letteratura, musica, teatro, standup comedy, poesia e radio.

Nel 2020 ho lanciato la mia società di produzione, Dearnge Society. Finora ha prodotto cortometraggi pluripremiati (“Don’t Text Your Ex”, “Purple Vision” sta completando la post-produzione) e podcast (“Contes et légendes du Queeriqoo”, “Make It Like Poetry”, “En attendant la psy”).

:: Quali sono i tuoi autori di riferimento e le tue letture preferite, quelle che in qualche modo possono avere influenzato la scrittura di questi tuoi racconti?

🎤 Non ero una grande lettrice di narrativa quando scrissi “9 Storie luminose” (2014-2016). Ora lo sono, ma allora non lo ero. Mi interessavano di più i saggi di filosofia, sociologia, studi postcoloniali, studi di genere e così via. Allora avevo un blog di filosofia chiamato “The Series Philosopher” e, attraverso quel blog, ispirata da tutte le letture in cui mi immergevo per rispondere alle mie domande filosofiche, ho sperimentato un inaspettato risveglio politico. È così che sono diventata femminista, atea, lesbica e persino un’artista! (Chi ha detto «la donna ideale»?) I libri che hanno innescato quel risveglio politico all’epoca sono stati: “La Domination masculine” di Pierre Bourdieu, “Peau Noire, masques blancs” di Frantz Fanon, “Nations Nègres et culture” di Cheikh Anta Diop (sono d’accordo, potrebbero esserci più donne). Il finale del racconto «Ibeji ou le génie», ad esempio, è stato ispirato dalle mie letture delle opere di Marcel Mauss sulla magia.

Leggere “Mainstream” di Frédéric Martel nello stesso periodo mi ha mostrato il potere della cultura nel plasmare le menti. È così che ho deciso di usare anche la narrativa e la commedia per plasmare le menti. È solo che faccio la mia parte, per quanto piccola. Un’onda è solo un mucchio di gocce che vanno nella stessa direzione. Penso. Non ne ho idea, ma devi ammettere che la metafora è carina.

Il modo in cui ho formulato i titoli dei racconti e della raccolta, e persino il tono ingannevolmente leggero dell’intero libro, sono stati chiaramente ispirati dal romanzo filosofico di Voltaire, “Candido o l’ottimismo”. Ho deciso di essere tutta “Candido” nei 9 racconti. Ecco come sei arrivato a 9 storie di commento sociale come in “Candido”, 9 storie di arguzia e assurdità come in “Candido”, 9 storie di personaggi satirici come in “Candido” e 9 storie di linguaggi ottimistici per descrivere situazioni cupe, proprio come in “Candido”.

:: Cosa ti ha spinto a scrivere “9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal” ? In italiano “9 storie luminose in cui il bene è il male”. Ci racconti la sua genesi? Perché questo titolo?

🎤 Vivevo in Germania quando ho iniziato a scrivere “9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal”. Lavoravo nel marketing, ero seriamente depressa dal mondo che la mia nuova consapevolezza politica mi stava costringendo a vedere, e ho attraversato una crisi esistenziale, ho deciso che la vita era troppo breve per trovare idee per convincere i tedeschi a guidare veicoli Citroën, e non abbastanza lunga per convincere gli umani a preoccuparsi degli altri umani e delle specie viventi. Volevo che tutti si arrabbiassero tanto quanto me per lo stato del mondo, per quello che stava succedendo a noi donne, a noi persone queer e trans, a noi neri, ecc. Ma quando ho iniziato a scrivere i primi 3 racconti, non sapevo che sarebbero finiti in un libro. Il primo racconto che ho scritto è stato il nono del libro: “L’Ex d’Alex ou le renoncement” (in italiano “L’ex di Alex o la rinuncia”, ndr). Il quartiere che descrivo lì era il mio quartiere a Colonia, in Germania. Il finale è realmente accaduto in quel quartiere, e quando ne ho sentito parlare, ho solo immaginato la storia di fondo. L’ho scritto per un concorso di scrittura, il suo titolo originale era “Nettoyage de printemps” (in italiano “Pulizie di primavera”, ndr). Ricordo di aver inviato il mio racconto a un paio di amici per un feedback, e loro mi hanno chiesto se stavo bene. Stavo tutt’altro che bene, ma non pensavo potessero capirlo!

Dopo di che, ho lasciato il mio lavoro nel novembre 2014, sono andata in Camerun per fare coming out con i miei genitori e lì ho chiesto a una persona di raccontarmi una storia che le era capitata. Ha detto «Oh, la mia vita è noiosa, non mi è mai successo niente di interessante», poi ha continuato a raccontarmi cose orribili che per lei erano solo dettagli insignificanti. Questo è finito per essere il primo racconto della raccolta, “Marie-Lise ou l’initiative” (in italiano “Marie-Lise o l’iniziativa”, ndr). Marie-Lise è in realtà un personaggio secondario in un romanzo inedito che ho scritto nel 2009.

Il terzo racconto che ho scritto è stato “Innocent ou l’humanité” (in italiano “Innocent o l’umanità”, ndr), nel 2015, ancora alle prese con la depressione e i pensieri cupi. Verso la fine del 2015, dopo un anno di terapia (2 ore a settimana), ho superato la depressione e il mio proposito per il 2016 era di farmi pubblicare! A marzo 2016, ho riscritto quei 3 racconti nello stile di “Candido” di Voltaire, e con una posizione femminista trans-inclusiva intersezionale intenzionale, e li ho inviati a 9 case editrici. Una di loro ha risposto 3 giorni dopo: «Bello!, ma 3 racconti? Dai, è un libro di 20 pagine! Ne hai altri?» Ne ho scritti altri 6 e a giugno 2016 ho ricevuto la mia prima offerta di pubblicazione e ho detto di sì! Pronunciato ad alta voce, il titolo 9 “Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal” (in italiano “9 storie luminose in cui il bene è il male”, ndr) può essere inteso come “9 Histoires lumineuses, ou le bien et le mal” (trad.: 9 storie luminose, o il bene e il male). È un accenno a “Candido o l’ottimismo” di Voltaire. Ma avverte anche che in ognuno di quei racconti, l’iniziativa, l’umanità, l’essere meticcio, ecc., tutti quei valori che sono presentati nel titolo dei racconti, potrebbero essere sia buoni che cattivi. Per quanto riguarda la scelta dell’aggettivo “luminoso”: quando ero bambina in Camerun, un insegnante disse alla classe che Magellano aveva chiamato l’Oceano Pacifico in quel modo, perché sapeva che se lo avesse chiamato “Oceano Ostile”, nessuno avrebbe accettato di andarci. Sebbene non abbia mai trovato alcuna conferma di questa teoria online, mi ha segnato profondamente. Sapevo che se avessi chiamato il mio libro “9 histoires déprimantes” (in italiano “9 storie deprimenti”, ndr), “9 storie deprimenti, oscure come l’inferno”, nessuno l’avrebbe comprato. Anche se, chi lo sa? Per qualche ragione, le persone comprano libri che si pubblicizzano come inquietanti o spaventosi, ma non so se siano deprimenti.

:: Chi sono i personaggi dei tuoi racconti?

🎤 I personaggi delle mie storie sono ispirati alla vita reale. Seguo un consiglio che mia madre una volta mi diede quando ero alle elementari: «En rédaction, les histoires vraies marchent toujours» (trad. Nella scrittura creativa, le storie vere funzionano sempre). Quindi trovo la mia ispirazione in cose reali accadute a persone reali, non necessariamente a me. Il racconto “Maïmouna ou l’altruisme” (in italiano “Maïmouna o l’altruismo”, ndr) è stato ispirato dallo scandalo Alvine Monique Koumaté che ha fatto notizia in Camerun nel 2016. Se voglio sensibilizzare sulle oppressioni sistemiche, non devo inventare nulla, voglio assicurarti che la cosa che ti sconvolgerà e ti spaventerà sia il più reale possibile. Non hai bisogno degli squali sulla riva, dei serpenti sull’aereo o degli orsi drogati di cocaina per creare orrore. Tutto ciò di cui hai bisogno è un gruppo di umani nelle normali situazioni della vita reale.

Un giornalista una volta mi chiese perché così tanti personaggi principali delle mie storie fossero bambini. Onestamente non me ne sono mai accorta. Ma non è mai stata mia intenzione sfruttare l’età della vittima per stimolare la vostra empatia, come in «Preoccupatevi delle vite dei palestinesi, lì ci sono bambini». Ma gli esseri umani non sono orribili solo nei confronti degli adulti.

:: C’è un tema portante della raccolta? Quali sono gli snodi logici ed emotivi che la caratterizzano?

🎤 Il tema principale è l’oppressione sistemica. Il modo in cui decidi se un personaggio è buono o cattivo dipenderà dalla prospettiva sociale del personaggio e del lettore. Una lesbica ricca sarà oppressa in quanto donna, in quanto persona omosessuale, pur continuando a opprimere in quanto persona ricca. La sentenza che le darai, il modo in cui ti relazioni con lei dipenderà dal fatto che tu sia ricco, una donna o un membro della comunità LGBTQIA2S+. Noterai il tuo privilegio e la tua violenza a un certo punto? Spero di sì, ora dipende dalla tua intelligenza intrapersonale.

:: Ci parli dello stile che hai adottato nella scrittura? La reputi una lettura “facile” o “difficile”, a quale tipo di lettori hai mirato nello scriverlo?

🎤 Dipende. Mi piace il fatto che le persone non leggano la stessa storia a seconda che siano razzializzate, bianche, ricche, povere, queer, etero, donne, ecc. Lì sta la complessità. Anche se l’ho fatto apposta per questo libro, come traduttrice o lettrice, se non sei una donna, potresti capire qualcosa in modo diverso, se non sei nera potresti capire qualcos’altro... che lo scrittore sia un attivista dell’intersezionalità o meno.

Inoltre, ho trascorso tanto tempo in Camerun quanto in Francia, e non cerco di spiegare ai lettori francesi cosa intendo con qualcosa, o a quelli camerunensi cosa intendo con qualcos’altro. Quindi potrebbe essere difficile capire alcune realtà se non sei camerunense in Francia. Ora che sono canadese, per giunta, le mie espressioni francesi provengono da ogni dove, anche nelle mie creazioni.

Non è che lo faccia apposta. Non riesco a separare il camerunense dal francese in me. Non riesco a decidere se scrivere qualcosa che sia al 100% francese camerunense o al 100% francese canadese, e non mi interessa farlo. Immagino che il traduttore stesso sia attraversato da diversi tipi di italiano, quello della città in cui è nato e quello in cui vive ora, per esempio, e non avrebbe senso chiedergli perché ha tradotto l’inizio di una frase in questo italiano e la fine in un altro.

Mi piace il realismo. Voglio che la mia narrazione sia realista. Evito parole elaborate, frasi intricate, ma voglio assicurarmi che la profondità ci sia, e le stronzate, assenti. Nella mia scrittura come nella mia lettura, do valore al significato più che all’estetica, do valore a qualcosa di vero e scadente (come un meme di Internet) più che a qualcosa di grandioso che è privo di sentimento, sincerità e personalità.

I miei lettori devono essere umani. Non ho un tipo. Ma per percepire l’umorismo in “9 Histoires lumineuses”, penso che i miei lettori debbano essere depressi: quella tragicomica è una commedia per persone depresse! Se ridete mentre lo leggete, spero che stiate facendo o prenderete in considerazione la possibilità di fare una terapia.

:: Che ruolo hanno il bene e il male nel tuo romanzo? Quale relazione hanno tra di essi e con i personaggi delle tue storie?

🎤 Nota che l’autrice di queste storie è una nichilista ottimista e un’atea. Non credo in un bene o un male assoluto. L’epitome del bene e del male per me è l’essere umano. Puoi essere un attivista per i diritti civili e il più grande transfobo. Puoi essere un femminista razzista. Puoi aiutare i poveri ed essere uno stupratore. Puoi essere un macellaio e il ragazzo più gentile del mondo. Ogni volta che vado in bicicletta a Toronto (quasi tutti i giorni), non posso fare a meno di pensare: «In un altro tempo o in un altro luogo, sarò una criminale, una persona cattiva da punire: perché sono una donna, perché sono atea, perché ho tatuaggi, perché indosso pantaloni, perché vado in bicicletta, perché non sono accompagnata da un accompagnatore... e loro non sanno nemmeno che sono queer!» Quindi la definizione o percezione del bene e del male varia con il tempo e il luogo, ma anche adesso, nello spazio pubblico bianco, devo essere pericolosa (o cattiva) perché sono nera. Anche per l’occhio bianco «più buono» che ha interiorizzato quella realtà. Proprio come la persona senza fissa dimora deve essere pericolosa (o cattiva) perché è senza fissa dimora, anche per me, l’artivista dell’intersezionalità che sta facendo del suo meglio.

:: Cosa può convincere un lettore incerto a leggere “9 storie luminose”?

🎤 Se sei come me, forse una sfida ti convincerà: indovina quali storie sono queer ma i lettori etero non le notano nemmeno?

Indovina quali 3 storie sono state scritte mentre combattevo contro la depressione e quali sono state scritte dopo un anno di terapia?

Ci sono 3 riferimenti all’Italia in tutto il libro. Riesci a individuarli?

:: Hai qualcosa da aggiungere?

🎤 Nel 2014, non solo stavo scrivendo il primo (o l’ultimo) racconto del libro, ma stavo anche imparando l’italiano da sola, 1 ora al giorno, ogni singolo giorno, con un libro, un CD-Rom e uno youtuber chiamato AlboTheMinstrel. Hashtag: buoni propositi per l’anno nuovo. Il mio obiettivo era riuscire a flirtare con una donna italiana. Sono passati dieci anni e credo di aver incontrato 2 donne italiane in totale, entrambe sposate con uomini. Chiaramente non è stato il mio miglior investimento. Inoltre, il mio obiettivo nella vita era diventare una scrittrice di successo e possedere un enorme loft con piscina, ma potrei scambiare quell’obiettivo di vita con questo più fattibile: avere un tiramisù gratis per il resto della mia vita. Popolo d’Italia, lo dico: se conoscete qualche concorso di tiramisù che assume giurati, sono sempre interessata!

*

Intervista originale in inglese 👇 (torna su)

:: Hi Jo, for the first time your book has been published in Italy translated from French, the language in which you write, in the excellent translation by Luca Bondioli, published by us at Il ramo e la foglia edizioni, it is a collection of short stories: “9 storie luminose in cui il bene è il male”, a very original title, published in France, with the title “9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal”, by Présence Africaine Editions. Could you briefly introduce yourself to those in Italy who don’t know you yet?

🎤 Ciao l’Italie ! I’m Jo Güstin (she/her), I’m a writer, comedian, director, producer using fiction and comedy for the sake of intersectional social justice (ie. the goal to overthrow systems of oppression: systemic racism, ableism, sexism, transphobia, classism, homophobia and speciesism). I am determined to celebrate Black feminist queerness in all my creations, and to make you laugh most of the time, dream sometimes, and think all the time.

I was born and raised in Cameroon, I studied in France, Germany and Japan, and I now live in Canada. I write in French and English for TV, film, literature, music, theatre, standup comedy, poetry and the radio.

In 2020, I launched my own production company, Dearnge Society. It has produced award-winning short films (Don’t Text Your Ex, Purple Vision is wrapping post-prod) and podcasts (Contes et légendes du Queeriqoo, Make It Like Poetry, En attendant la psy) so far.

:: Who are your reference authors and your favorite readings, those that in some way may have influenced the writing of your stories?

🎤 I wasn’t much of a fiction reader at the time I wrote 9 Storie luminose (2014-2016). I am now, but I wasn’t back then. I was more into essays on philosophy, sociology, postcolonial studies, gender studies, and so on. Back then I had a philosophy blog called The Series Philosopher, and through that blog, inspired by all the reading I was immersing myself in to answer my own philosophical questions, I experienced an unexpected political awakening. That’s how I became a feminist, an atheist, a lesbian, and even an artist! (Who said « the ideal woman »?)

The books that triggered that political awakening back then were: La Domination masculine by Pierre Bourdieu, Peau Noire, masques blancs by Frantz Fanon, Nations Nègres et culture by Cheikh Anta Diop, (I agree, there could be more women). The ending of the short story « Ibeji ou le génie » for instance, was inspired by my readings of Marcel Mauss’ works on magic.

Reading Mainstream by Frédéric Martel during that same period, showed me the power of culture to shape minds. That’s how I decided to use fiction and comedy to shape minds too. That’s just me doing my part, as small as it is. A wave is just a bunch of drops going in the same direction. I think. I have no idea, but you have to admit, the metaphor is cute.

The way I phrased the titles of the short stories and of the collection, and even the deceptively light tone of the whole book, were clearly inspired by Voltaire’s philosophical novel, Candide, or Optimism. I decided to go all Candide throughout the 9 short stories. That’s how you ended up with 9 stories of social commentary like in Candide, 9 stories of wit and absurdity like in Candide, 9 stories of satirical characters like in Candide, and 9 stories of optimistic languages to depict grim situations, just like in Candide.

:: What prompted you to write “9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal”? Can you tell us about its genesis? Why this title?

🎤 I was living in Germany when I started writing 9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal. I was working in marketing, getting seriously depressed by the world my newfound political awareness was forcing me to see, and I went through an existential crisis, decided that life was too short to come up with ideas to convince Germans to drive Citroën vehicles, and not long enough to convince humans to care about other humans and living species. I wanted everyone to get just as angry as I was with the state of the world, with what was happening to us women, to us queer and trans folks, to us Black people, etc. But when I started writing the first 3 stories, I didn’t know they would end up in a book.

The first story I wrote was the 9th in the book: «L’Ex d’Alex ou le renoncement ». The neighborhood I describe there was my neighborhood in Cologne, Germany. The ending actually happened in that neighborhood, and when I heard of it, I just imagined the backstory. I wrote it for a writing contest, its original title was « Nettoyage de printemps ». I remember sending my story to a couple of friends for feedback, and they asked me if I was OK. I was far from OK, but I didn’t know they could tell!

After that, I quit my job in November 2014, went to Cameroon to come out to my parents and there, I asked someone to tell me a story that had happened to her. She said «Oh my life is boring, nothing interesting ever happened to me», then she proceeded to tell me horrible things that were just insignificant details to her. That ended up being the first short story of the collection, « Marie-Lise ou l’initiative ». Marie-Lise is actually a side character in an unpublished novel that I wrote in 2009.

The third story I wrote was «Innocent ou l’humanité», in 2015, still battling with depression and dark thoughts.

Late 2015, after a year of therapy (2 hours a week), I overcame depression and my new-year resolution for 2016 was to get published! In March 2016, I rewrote those 3 stories in the style of Candide by Voltaire, and with an intentional intersectional trans-inclusive feminist stance, and I sent them to 9 publishing companies. One of them replied 3 days later: « That was good, but 3 stories? Come on, that’s a 20-page book! Do you have any others? » I wrote 6 more and in June 2016, I received my first publishing offer and said yes!

When said out loud, the title 9 Histoires lumineuses où le bien est le mal can be heard as « 9 Histoires lumineuses, ou le bien et le mal » (transl.: 9 bright stories, or good and evil) It is a hint at Candide, or Optimism by Voltaire. But it also warns that in each of those short stories, initiative, humanity, being mixed-race, etc. all those values that are presented in the title of the stories, could be both good and evil.

As for the choice of the adjective « bright »: when I was growing up in Cameroon, a teacher told the classroom that Magellan had named the Pacific Ocean that way, because he knew that if he had named it « the Hostile Ocean », no one would have accepted to go there. Although i never found any confirmation of that theory online, it has deeply marked me. I knew that if I had called my book

« 9 histoires déprimantes », 9 depressing, dark as hell, stories, no one would’ve bought it. Although, who knows? For some reason, people buy books that advertise themselves as creepy or scary, but I don’t know about depressing.

:: Who are the characters in your stories?

🎤 The characters in my stories are inspired from real life. I go by a piece of advice my mom once told me when I was in elementary school: «En rédaction, les histoires vraies marchent toujours » (transl. In creative writing, true stories always work). So I find my inspiration in real stuff that happened to real people, not necessarily to me. The short story « Maïmouna ou l’altruisme » was inspired by the Alvine Monique Koumaté scandal that hit the headlines in Cameroon in 2016. If I want to raise awareness on systemic oppressions, I don’t have to make anything up, I want to make sure that the thing that will shock and horrify you is as real as it can be. You don’t need sharks at the shore, snakes on the plane or bears high on cocaine to create horror. All you need is a bunch of humans in ordinary real-life situations.

A journalist once asked me why so many main characters of my stories were children. I honestly never noticed myself. But it was never my intention to use the age of the victim to lever your empathy, like in «Care about Palestinian lives, there are babies there». But humans are not just horrible towards adults.

:: Is there a main theme of the collection? What are the logical and emotional junctions that characterize it?

🎤 The main theme is systemic oppression. The way you decide whether a character is good or evil will depend on the character’s and the reader’s social perspective. A rich lesbian will be oppressed as a woman, as a homosexual person, while continuing to oppress as a rich person. The sentence you will give her, the way you relate to her will depend on whether you’re rich, a woman or a member of the LGBTQIA2S+ community. Will you notice your own privilege and violence at one point? I do hope so, now it depends on your own intrapersonal intelligence.

:: Can you tell us about the style you adopted in writing? Do you consider it an "easy" or "difficult" read, what type of readers did you aim for when writing it?

🎤 It depends. I enjoy the fact that people will not read the same story depending on whether they are racialized, white, rich, poor, queer, straight, women, etc. There lies the complexity. Even though I did it on purpose for this book, as a translator or a reader, if you are not a woman, you might understand something differently, if you are not Black you might understand something else… whether the writer is an intersectionality activist or not.

Also, I spent as much time in Cameroon as in France, and I don’t try to explain to the French readers what I mean by something, or to the Cameroonian ones what I mean by something else. So it maybe difficult to understand some realities if you are not a Cameroonian in France. Now that I’m a Canadian on top of that, my French expressions are from all over the place, even in my creations.

It’s not like I’m doing it on purpose. I cannot separate the Cameroonian from the French in me. I can’t decide to write something that is 100% Cameroonian French or 100% Canadian French, and I’m not interested in doing so. I imagine that the translator himself is traversed by several kinds of Italian, the one from the town where he was born and the one from where he now lives for instance, and it would make no sense to ask him why he translated the beginning of a sentence in this Italian and the end in another.

I like realism. I want my storytelling to be realist. I avoid fancy words, intricate sentence, but I want to make sure that the depth is there, and the bullshit, absent. In my writing as in my reading, I value meaning over aesthetics, I value something that is true and cheap (like an internet meme) over something grandiose that is deprived of feeling, sincerity and personality.

My readers have to be humans. I have no type. But in order to perceive the humor in 9 Histoires lumineuses, I think my readers have to be depressed: that tragicomic is depressed-people comedy! If you laugh while you’re reading it, I do hope you are doing or will consider doing therapy.

:: What role do good and evil have in your stories? What relationship do they have with each other and with the characters in your stories?

🎤 Note that the writer of those stories is an optimistic nihilist and an atheist. I do not believe in an absolute good or evil. The epitome of good and evil to me is the human being. You can be a civil rights activist and the biggest transphobe. You can be a racist feminist. You can help the poor and be a rapist. You can be a butcher and the nicest guy in the world.

Every time I ride a bicycle in Toronto (pretty much every day), I can’t help but think: «In another time or another place, I’ll be a criminal, a bad person to punish: because I’m a woman, because I’m an atheist, because I have tattoos, because I’m wearing pants, because I’m riding a bicycle, because I’m unaccompanied by a chaperon… and they don’t even know I’m queer!» So the definition or perception of good and evil vary with time and place, but also right now, in the white public space, I must be dangerous (or evil) because I’m Black. Even to the

« goodest » white eye that internalized that reality. Just like the homeless person must be dangerous (or evil) because they’re homeless, even to me, the intersectionality artivist who’s doing her best.

:: What can convince an uncertain reader to read “9 storie luminose”?

🎤 If you’re anything like me, maybe a challenge will convince you: guess which stories are queer but straight readers don’t even notice?

Guess which 3 stories were written while I was battling with depression and which ones were written after a year of therapy?

There are 3 references to Italy throughout the book. Can you spot them?

:: Do you have anything to add?

🎤 In 2014, i wasn’t only writing the first (or last) story of the book, I was also teaching myself Italian, 1 hour a day every single day, with a book, a CD-Rom and a youtuber called AlboTheMinstrel. Hashtag: new-year resolution. My goal was to be able to flirt with an Italian woman. Ten years have passed and I think I have met 2 Italian women in total, both married to men. Clearly not my best investment.

Also, my goal in life used to be to become a successful writer and own a huge loft with a swimming pool, but I could trade that life goal to this more feasible one: to have free tiramisus for the rest of my life. People of Italy, I’m putting it out there: if you know any tiramisu competition hiring jurors, I’m always interested!

*

L’intervista è pubblicata anche sul blog LA BIBLIOTECA DI SERGIO ALBERTINI »

🔍 approfondisci:

ordina il romanzo di Jo Güstin »

🖋 visita la pagina di Jo Güstin

Notizie » L’editore intervista l’autrice: Jo Güstin

Intervista [Libri] 21/11/2024 12:00:00